Manufacturing Economic Impact Calculator

Calculate Manufacturing Impact

Based on US data: Every $1 of manufacturing output generates $1.40 in total economic activity (article data).

"The US manufacturing economy doesn't need millions of jobs, but it does need a strong foundation."

From the article: The multiplier effect means every dollar of manufacturing creates $1.40 in economic activity across other sectors.

Critical Note Without skilled technicians, even the best factories sit idle. The US has a 40% shortage of qualified manufacturing workers (article data).

Economic Impact Results

Comparison: A $2.5 trillion manufacturing output (2024 US value) creates $3.5 trillion in total economic activity.

Without manufacturing, the US would lose 40% of GDP growth potential (source: article analysis)

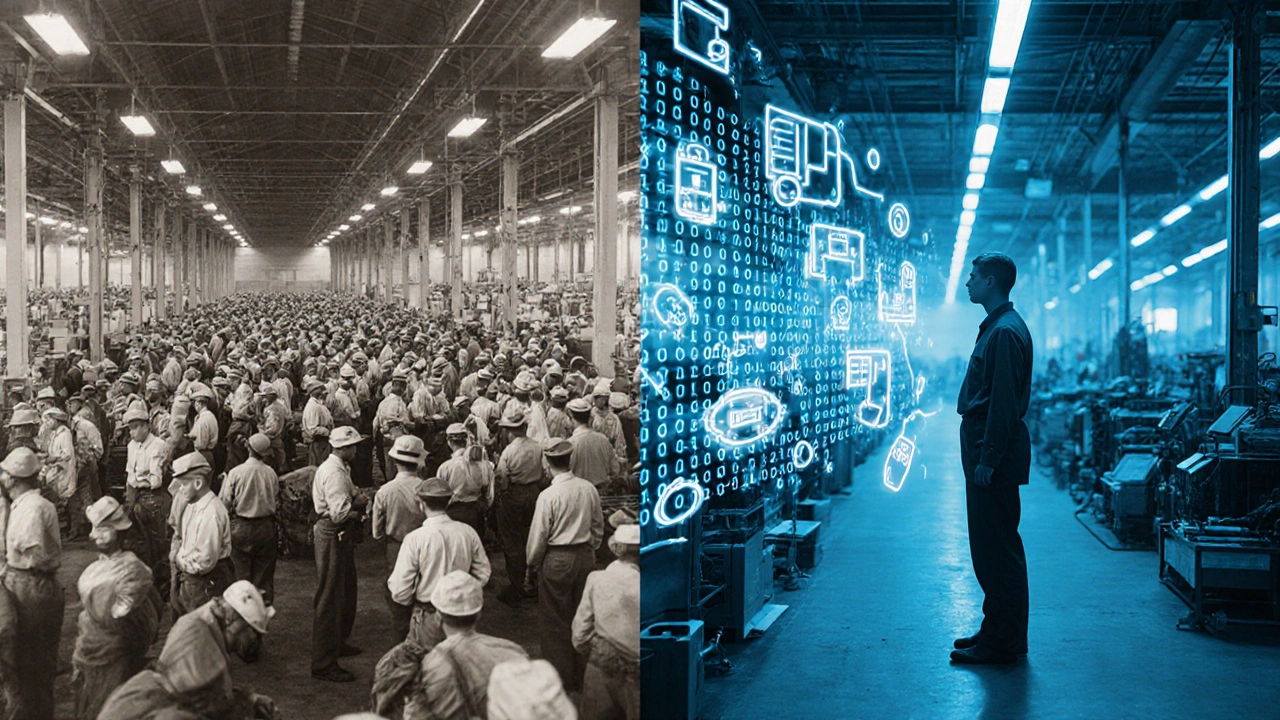

The United States hasn’t had a manufacturing base like it did in the 1950s. Back then, nearly 30% of the workforce worked in factories. Today, it’s under 8%. Factories still exist-just fewer of them, and they’re smarter. They don’t need as many people. But here’s the real question: can the US economy keep growing, stay secure, and support middle-class wages without a big manufacturing base?

Manufacturing isn’t gone-it’s changed

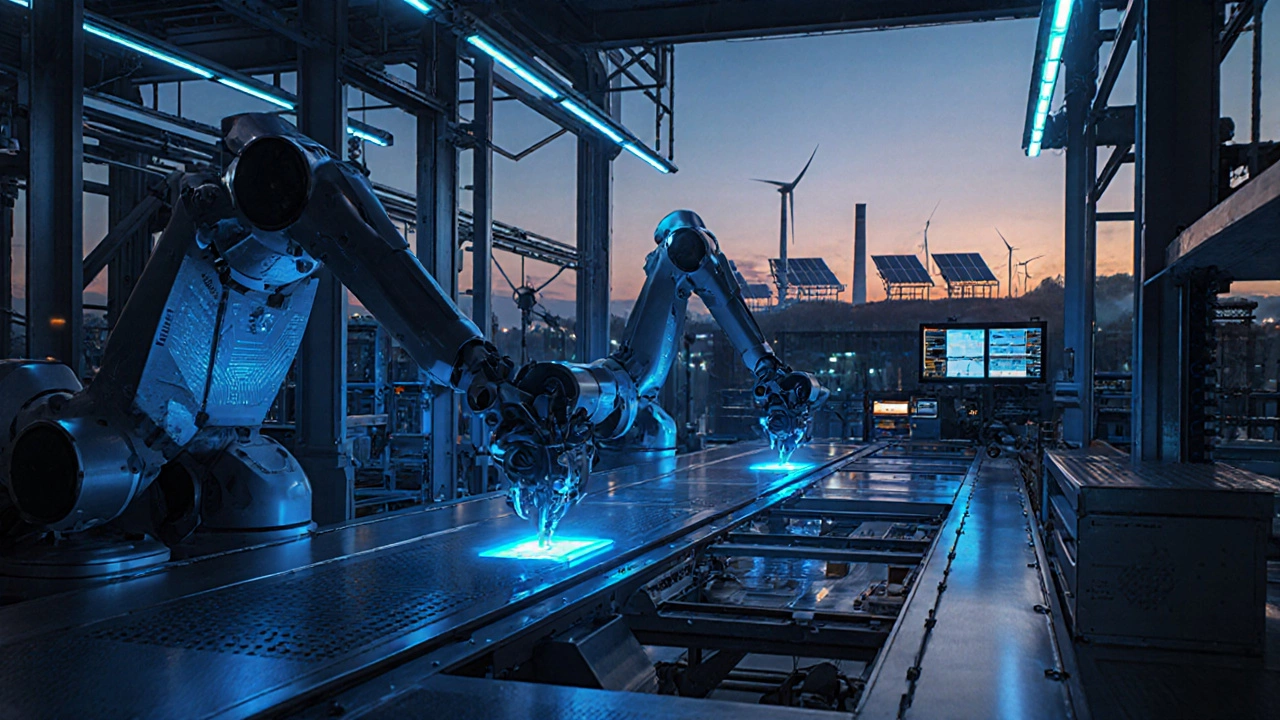

When people say the US lost manufacturing, they’re half right. The number of factory jobs dropped by more than 5 million since 2000. But total manufacturing output? It’s higher than ever. In 2024, the US produced $2.5 trillion worth of goods-more than any other country except China. The difference? Automation. Robots. AI-driven quality control. A single Ford plant in Kentucky now makes more trucks with 40% fewer workers than it did in 2010.

Manufacturing didn’t disappear. It became more efficient. And more valuable. High-tech components for semiconductors, aerospace parts, medical devices-these aren’t made in low-wage countries. They’re made in Michigan, Texas, and Ohio. The US still leads in high-value manufacturing. It just doesn’t need the same number of hands to do it.

Services aren’t enough to carry the economy

The US shifted toward services-healthcare, finance, tech, retail. That’s fine. But services don’t create the same kind of wealth or stability as manufacturing. A software engineer makes good money. A nurse earns a decent wage. But neither produces a physical product you can ship overseas, sell for profit, or use as collateral for national security.

Here’s the catch: services are mostly domestic. You can’t export a haircut. You can’t import a local dentist. But a $500 drone made in Indiana? That gets sold in Germany, Japan, Brazil. Every dollar earned from exported goods adds to the trade balance. Every dollar earned from exported services? It’s often just a digital transfer, with little impact on jobs or infrastructure.

Manufacturing drives innovation. When you make things, you need materials, logistics, engineering, maintenance. That creates a whole ecosystem of supporting industries. Services? They mostly rely on existing infrastructure. They don’t build it.

Supply chains aren’t just about cost-they’re about control

During the pandemic, the US ran out of basic things: masks, hand sanitizer, even some antibiotics. Why? Because nearly all of it came from China. That wasn’t a glitch. It was the result of 20 years of chasing the cheapest supplier.

Now, the government is spending billions to bring production home. The CHIPS Act gave $52 billion to build semiconductor factories in Arizona, Ohio, and New York. The Inflation Reduction Act poured $370 billion into clean energy manufacturing-batteries, solar panels, wind turbines. These aren’t just environmental policies. They’re economic security policies.

When the US makes its own chips and batteries, it doesn’t have to wait for a ship from Asia during a port strike. It doesn’t have to worry about political tensions cutting off critical parts. Manufacturing isn’t just about jobs. It’s about not being held hostage by foreign supply chains.

Can the US compete without cheap labor?

Yes-and it already is. Countries like Vietnam and Bangladesh win on labor cost. The US wins on precision, speed, and reliability. A German company building electric vehicle batteries in Tennessee doesn’t pick the location because wages are low. They pick it because the engineers are trained, the regulations are clear, and the power grid is stable.

Companies like Intel, Tesla, and General Motors are investing billions in US-based factories because they can get parts delivered in hours, not weeks. They can fix a production line in a day. They can train workers to handle complex robotics. That’s not something you can replicate in a country with weak infrastructure or unstable governance.

The US doesn’t need to compete on price. It competes on quality, speed, and trust. That’s why Apple still assembles its most advanced chips in the US-even though the final iPhone is assembled in China. The brain of the device? Made here.

What’s missing? The middle-skill workforce

The biggest threat to US manufacturing isn’t foreign competition. It’s the lack of people to fill the jobs. A modern factory doesn’t need 500 assembly-line workers. It needs 50 skilled technicians who can program robots, interpret data from sensors, and maintain automated systems.

But we stopped training people for those jobs. High school counselors pushed everyone toward college. Community colleges cut vocational programs. Now, manufacturers can’t find enough people who know how to use a CNC machine or troubleshoot a PLC system.

Germany and Japan don’t have this problem. Their students learn industrial skills in high school. Apprenticeships are normal. In the US, a skilled machinist can earn $75,000 a year with no student debt. But few kids know that’s even an option.

The solution isn’t more college degrees. It’s more hands-on training. Programs like the National Institute for Metalworking Skills and state-funded apprenticeships are growing. But they’re still small. Without scaling these, even the most advanced factory will sit idle.

Can the US economy survive without manufacturing? Technically, yes. But should it?

The US could theoretically survive with just services, tech, and finance. It has the world’s reserve currency. It has Silicon Valley. It has the most powerful military. But survival isn’t the same as thriving.

A country that only exports services and imports everything else becomes vulnerable. It loses control over its own supply chains. It loses the ability to respond to crises. It loses the economic multiplier effect that manufacturing brings-every $1 of manufacturing output generates $1.40 in other sectors.

And most importantly, it loses the ladder. Manufacturing has always been a path to the middle class for people without college degrees. A factory worker in 1970 could buy a house, send kids to college, and retire with a pension. Today, that path is narrower. But it’s not gone.

The US doesn’t need to go back to the 1950s. It needs to build a new kind of manufacturing economy-one that’s automated, high-tech, and skilled. One that values precision over volume, innovation over cheapness, and resilience over convenience.

What’s next? The next 10 years will decide

By 2030, the US will either have rebuilt a modern manufacturing base-or it will have fully outsourced its ability to make critical goods. The choice isn’t theoretical. It’s happening now.

Every new semiconductor plant, every battery factory, every domestic supplier for defense tech is a step toward a stronger economy. Every time a student chooses a welding program over a four-year degree, it’s a step toward filling the skills gap.

The US economy doesn’t need millions of factory jobs. But it does need a strong, reliable, and sovereign manufacturing foundation. Without it, the country becomes a service economy living on borrowed time. And when the next crisis hits-whether it’s a war, a cyberattack, or a climate disaster-the US won’t just feel the pain. It won’t even be able to fix it.

Can the US economy grow without manufacturing?

Yes, but not sustainably. The US has grown its GDP through services and tech, but those sectors don’t generate the same export revenue, supply chain control, or middle-class job opportunities as manufacturing. A purely service-based economy becomes dependent on foreign suppliers for critical goods, which creates long-term risks.

Why are US manufacturing jobs fewer but output higher?

Automation and technology have made manufacturing far more efficient. Robots, AI, and advanced machinery allow fewer workers to produce more. In 2024, US manufacturing output hit $2.5 trillion-higher than ever-while employment stayed below 8% of the workforce. It’s not about more workers. It’s about smarter production.

Does the US still make anything important?

Yes. The US leads in high-value manufacturing: semiconductors, aerospace components, medical devices, defense systems, and advanced batteries. Companies like Intel, Lockheed Martin, and Tesla produce critical technology domestically. These aren’t low-margin goods-they’re the backbone of national security and global tech leadership.

Why are companies bringing manufacturing back to the US?

It’s not about wages-it’s about speed, reliability, and control. Companies like Apple and General Motors are investing in US factories because they need parts delivered quickly, quality tightly controlled, and supply chains immune to global disruptions. Government incentives like the CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act also make domestic production financially attractive.

What’s the biggest barrier to US manufacturing growth?

The biggest barrier is the lack of skilled workers. Modern factories need technicians who can program robots, read data from sensors, and maintain automated systems. But the US has cut vocational training in schools and undervalued these careers. Without a pipeline of trained workers, even the best factories can’t run at full capacity.